Point Lobos (Big Sur 18)

Over 20 species of land mammals live at Point Lobos, and several other species – such as coyotes and mountain lions – occasionally enter the Reserve from surrounding areas. These include ground and gray squirrels, pocket gophers, black-tailed mule deer and brush rabbits.*

Point Lobos Foundation: https://www.pointlobos.org

Point Lobos (Big Sur 17)

Point Lobos (Big Sur 16)

Detail of clumps of Trentepholia on Monterey Cypress in Point Lobos.

Point Lobos (Big Sur 15)

Point Lobos (Big Sur 14)

The favorite of many visitors, The Cypress Grove Trail winds through one of only two naturally growing stands of Monterey Cypress trees remaining on earth.

These cypresses, which formally extended over a much wider range, withdrew to these fog-shrouded headlands as the climate changed with the close of the Pleistocene epoch 15,000 ears ago.

The orange, velvety “stuff” especially noticeable on trees and rocks of the shadowed, north-facing slopes is a species of green algae called trentepholia. Its orange color comes from carotene, a pigment which also occurs in carrots. The plant does not harm the trees.* (Point Lobos State Natural Reserve - park guide)

Point Lobos (Big Sur 13)

The southern perimeter of Point Lobos State Reserve ends at Pelican Point. From the vantage point on the trail is Gibson Beach and the Carmel Highlands leading to Big Sur.

Point Lobos is bookended by two spectacular beaches, Gibson Beach to the south and Monastery Beach to the north. Monastery Beach has a sudden drop-off into deep waters making it a popular place for scuba diving.

Point Lobos (Big Sur 12)

Visitors to Point Lobos look out on an enormous sea stack (Bird Island).

Point Lobos (Big Sur 11)

Point Lobos (Big Sur 10)

Sea caves and two arches in granodiorite near Pelican Point with homes in the Carmel Highlands in the background. Waves have cut through beneath following a zone of weakness created by vertical fractures.

Harbor Seal and her new born pup take shelter in a sea cave in China Cove.

Point Lobos Legends (Big Sur 9)

Point Lobos, the locale of Stevenson’s Treasure Island has been the focal point of many odd tales. People have reported seeing all manner of nature spirits, Varying from beautiful devas (angels) with brilliantly flashing wings and talons. The sea spirits are reputedly the most dangerous to mankind, for they are always dragging people into the sea and drowning them. They do this not malevolently but playfully.*

*A Wild Coast & Lonely—Big Sur Pioneers by Rosalind Sharpe Wall

Stories of nature spirits haunting the Coast have gone back as far as anyone can remember. First there were the fog-ghosts, whom the Indians loved and made friends with. These ghosts were lonely and sad. The Indians went out at night from the Mission to meet them in the woods and cheer them up. When the Franciscans fathers learned of this, they followed them out one night and performed an exorcism. The fog-ghosts, howling, departed and the Indians mourned. According to legend, the Father who performed the exorcism went mad, ran over a cliff and was drowned at sea near Point Lobos.*

Point Lobos (Big Sur 8)

Point Lobos is just south of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, and at the north end of the Big Sur coast of the Pacific Ocean. Point Lobos nearly became the site of a town. In 1896, the Carmelo Land and Coal Company subdivided the land into 1,000 lots and named the new town "Carmelito". Engineer Alexander Allan purchased the land and over many years bought back the lots that had been sold and erased the subdivision from the county records.

The two native cypress forest stands are protected, within Point Lobos State Reserve and Del Monte Forest. The natural habitat is noted for its cool, moist summers, almost constantly bathed by sea fog.

The Allan family retained the land to the east of Highway 1. Eunice Allan Riley, one of Alexander's three daughters, repurchased the last subdivided lots in the 1950s. In 1960, 750 acres (300 ha) underwater acres were added as the first marine reserve in the United States. The marine reserve was designated an ecological reserve in 1973, and in 1992, was added to the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, the largest in the nation.* Wikipedia

The Bohemians of Carmel and Big Sur

Gathering together George Sterling, Robinson Jeffers, we may begin to thread the needle of spirit of Big Sur with Jaime De Angulo. If Sterling was the misplaced Victorian gentleman in an emerging age of literary modernism, and Jeffers the modern who built a monument Tor House and Hawk Tower, made of granite boulders, a fortress set against the storms and the howling winds of the Pacific Ocean, De Angulo was the Poet Vaquero, a scholarly cowboy at home in the raw wildness amid the madrone and manzanita, chaparral, the dust and rattlesnakes of Alta California.

…he hungered for what stretched outside the granite pediments and towers, well past the garrison walls: wilderness, wild animals, Indians, medicine song, and a storytelling tradition that might be ten thousand years old, alive in the human voice.*

Rosalind Sharpe Wall describes her first encounter with Jaime in A Wild Coast and Lonely-Big Sur Pioneers:

Jaime de Angulo was a medical doctor turned anthropologist who bought a ranch at Big Sur in 1914 from Roche Castro. His appearance, in the 1920s when I first saw him, was dramatic in the extreme. He came riding down our hill to Rainbow Lodge on a black stallion, along with a huge turquoise-studded Indian silver conch belt from New Mexico. His long black flowing in the wind, his blue eyes flashing, he was beautiful rather than handsome and was given to passionate gestures, speaking with his hands as well as his tongue. And he talked rapidly, brilliantly, usually about linguistics, the American Indians, or Freud.

*Tracks Along the Left Coast, Jaime De Angulo & Pacific Coast Culture by Andrew Schelling

Growing up in Big Sur from childhood Sharpe had the experience of knowing Jaime over many years and writes unsparingly of his dramatic personal decline:

But Jaime had also a dark side, a perverse and contradictory side—and his enemies called him crazy, bohemian, drunken, dangerous even a devil… His dramatic sense, his need to play a role, to be a buffoon, a star, a madman, a tragic figure, a rebel, a martyr, ruled his life and made it in the end a wasteland, a tragedy—except for his work which was unquestionably the work of a genius.

De Angulo was always brilliant and inquisitive but his methods could be undisciplined and his behavior unpredictable. His conflicts with the newly formed Anthropology Department at UC Berkeley were acknowledged in his book:

Indians in Overalls

…I proposed to record some songs on my phonograph machine. I carried around one of the old Edison phonographs with a big horn. You made the records on wax cylinders with a special cutting jewel needle ; then to play them you changed to a needle with a rounded point. The whole contraption was crude and primitive compared to modern methods. It was hard enough to operate in a laboratory; imagine it in the open, competing with the wind; the horn would swing around; we cursed—-How I sweated and labored over those Indian songs, and the fortune I spent on broken records…That was before the days of amplification; later on new methods appeared; flat disks, unbreakable and permanent; wonderful improvements…but the Indians are gone, no more singing to record.

The passage is footnoted by this:

The University (of Berkeley) would not help me; took no interest; would not even give me enough money to have the records transcribed and made permanent on modern disks. Decent anthropologists don’t associate with drunkards who go rolling in ditches with shamans.

De Angulo was a gifted writer but his novels, poetry and stories were all published posthumously.

Jaime DeAngulo Rides Again

Lisa Scola Prosek composed an opera based on DeAngulos’s 1927 novel The Lariat.

Originally developed in cooperation with Louise Miranda Ramirez, an elder of the Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation of Monterey County, Prosek’s work combined Esselen language lyrics with melodies that De Angulo had researched and preserved, and then retooled them into her musical score.*

*repeatperformances.org, opera, “The Lariat” at Thick House, January 31, 2015

Robinson Jeffers' Tor House in Carmel

Jeffers as he said himself, was deeply influenced by the land which became his locale, but in reality it was an extraordinary connection of locale and man; for without Jeffers the landscape could never have been voiced in the way it was and without the landscape he could never have found his own true voice. His themes were classical, timeless and always symbolic; this was the point so many people missed.*

*A Wild Coast & Lonely — Big Sur Pioneers by Rosalind Sharpe Wall

Tor House was build with low ceilings and doors to decrease the wind resistance (and to conserve heat, which was supplied only by the fireplaces).**

Una Jeffers describes the tower:

I am writing from my little oaken sitting room on the second floor where at one end an oriel window juts seaward, at the other a spinet with piles of old Gaelic ballads stands beside an open fire.

If I climb the winding stair two stories higher I can look from the top of the turret southwards and see beyond the river mouth and Point Lobos wisps of cloud caught in the gentle folds of the Santa Lucia Mountains; northward lies the village with the Del Monte Forest beyond, and to the east the fertile Carmel Valley with the old amber-colored Spanish Mission where its founder Father Serra sleeps, at its foot.**

Hawk Tower rose out of our dreams of old Irish towers but we have seen in the eyes of our friends, as we have so often climbed the turret with in the last dozen years, that in many hearts is the mirage of some symbolic tower—citadel, belfry or beacon light.**

**Creating Carmel, The Enduring Vision by Harold & Ann Gilliam

Una Jeffers brought this Celtic Cross from a graveyard in Ireland. The stone walls in Tor House are filled with objects like decorative tiles and objects collected from their travels far from home. This stone cross and tiles are inlaid in the path through the garden.

Tor House, once solitary on Point Carmel is part of a sprawling upscale suburb with a broad mixture of architectural styles.

Carmel Point. The view from Tor House looking out to the Pacific Ocean.

The Bohemians of Carmel and Big Sur (Part 2)

…and whoever speaks across the gap of thousand years will understand that he has to speak of permanent things, and rather clearly too, or who would hear him? Robinson Jeffers

What needs most simply to be stressed is that—for all his lyric flights, narrative probings, historical pronouncements, and excoriations of human solipsism in all its individual and collective forms—Jeffers believed poetry should bring us to reality rather than transform or replace it. Poetry’s task, he said is to engage “permanent things” and reveal the permanence beyond the poem.*

Monterey journalist and Big Sur native Rosalind Sharpe Wall published her memoir of the the settlers, ranchers, homesteaders and artists she knew growing up in Big Sur. She describes the arrival of Robinson Jeffers to the area and the initial impressions that lead to the themes and somber tones of his poetry.

George Sterling’s enthusiastic, lyrically descriptive letters to Jeffers, describing the Sur and its isolated inhabitants, struck a chord and after the Jeffers lost their first child, Maeve, they moved to Carmel where he and Una walked down to Ocean Avenue on December 20, 1914, and took the horse drawn mail stage that left before dawn and arrived at Pfeiffer’s Resort in the Big Sur by dark.*

Edward Weston photograph of Jeffers and his twin sons Donnan and Garth.

I asked Jeffers what his first impression of the Coast was on that wintery day. “The Coast seemed solitary; there was a light rain. I would not have written the same kind of thing if it had been a different kind of landscape. My first impression of the Coast: it was winter time, darker and more sinister. I was shocked later when I saw Big Sur in the summer and the hills golden. Perhaps I shouldn’t have said sinister; rather hostile to its inhabitants.”*

Corbett Grimes was the mail stage driver, as fate would have it, and he was a garrulous young man recently arrived from Liverpool who was later to become known as the Coast’s best storyteller. He had come to visit his uncle, Ed Grimes, who had married Ellen Post, at his ranch on the high trail below BigSur, and he was all agog with the wonders of the place which exceeded anything he had ever heard in England of the wonders of the Wild West. On their way down the Coast, Grimes regaled his fascinated passenger with dramatic tales, pointing out every landmark where an accident, murder, suicide, or lynching had occurred.

Naturally he gave Jeffers the impression that the Coast was all violence, all somberness and brooding.*

*The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers, Edited by Tim Hunt, Stanford University Press 2001

**A Wild Coast and Lonely, Big Sur Pioneers, Rosalind Sharpe Wall

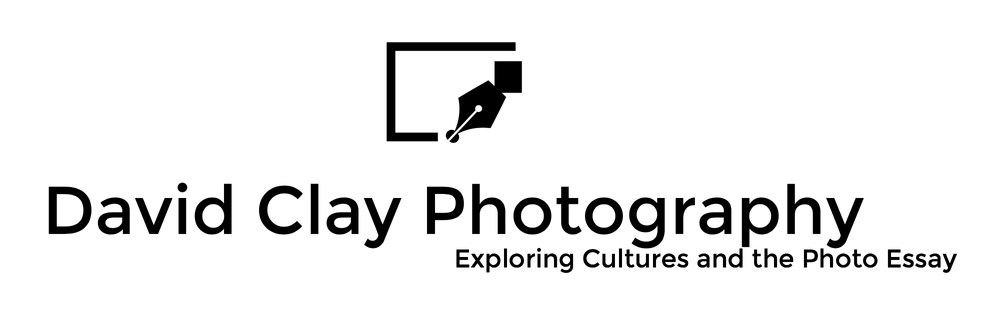

Una and Robinson Jeffers and his English bulldog Haig at Tor House

James Karman, Jeffers biographer sums up his art and legacy:

…no one else devoted himself or herself to bringing an entire landscape to life in verse; and no one else was so persuasive in doing so that he or she can be credited with helping to inspire the modern environmental movement. With a combination of scientific acumen and aboringal love for the Monterey—Carmel—Big Sur coast of California, Jeffers uncovered the terroir, the spirit and inner life of the region—as revealed in its topography, its flora, fauna, and people.

Robinson Jeffers, Poet and Prophet

The Bohemians of Carmel and Big Sur (Part 1)

Bohemians are portrayed as unbridled, carefree rebels of the established order. American artists at the turn of the century may have sought out an arcadian paradise, but they brought the obsessions of making a serious art, and serious art in their time was tragedy.

Greta Wiesenthal by Rudolf Jobst. Image from Wikipedia Commons.

George Sterling: The King of Bohemia

“He was the proton around which the rest of us revolved as electrons.” Vernon Kellogg

Successive waves of claims by artists and individuals have been made on the Big Sur area. George Sterling is responsible for establishing the artists colony in Carmel. From Sterling came Robinson Jeffers, Henry Miller escaping Paris at the dawn of WW II, Jack Kerouac and the Beats, The Big Sur Folk Festivals, Ansel Adams, Aldous Huxley, Fritz Perls and tourists from every corner of the earth.

George Sterlings move from San Francisco to Camel is the place to begin a look for the artistic claims on the Genius Loci of Carmel and Big Sur.

Cheap rent and affordable food

Bohemians in San Francisco at the turn of the century flocked to the Montgomery Block where rents were low in the abandoned offices and spaghetti houses like Coppa’s offered inexpensive food and wine. Poppa Coppa provided artists with meal chits that could bridge them financially between sales of paintings and poetry. George Sterling held court many evenings at Coppa’s Restaurant with the writers, poets, painters and anarchists living in the area. Working with his uncle, a real-estate developer in Oakland, Sterling’s real aspiration was to be a poet.

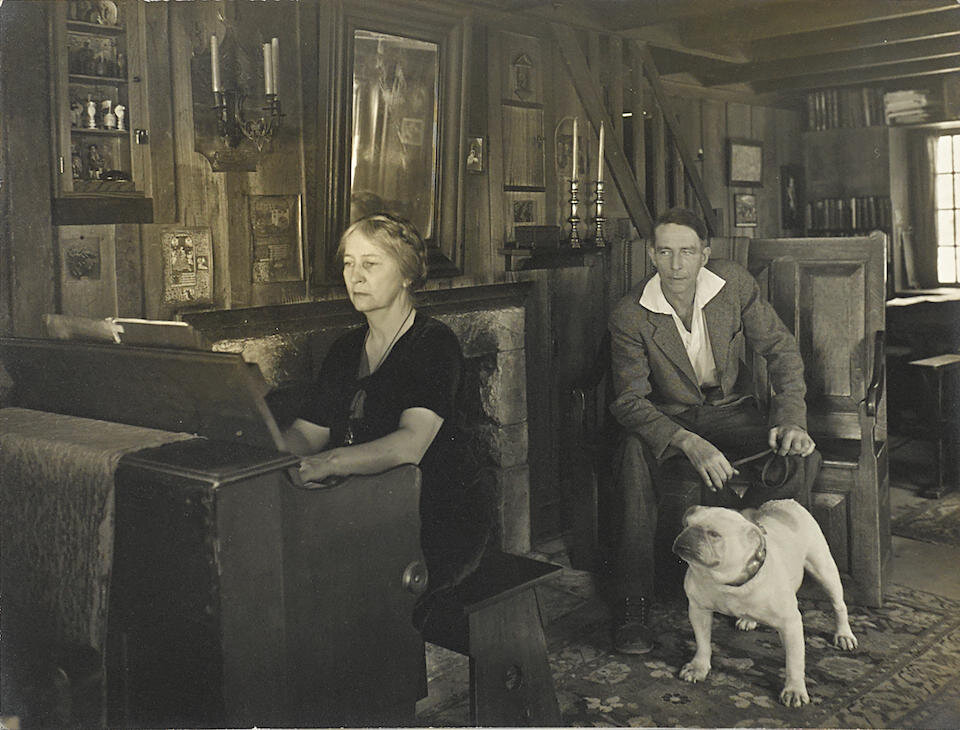

Felix Piantanida And Poppa Coppa Standing At The Bar In Coppa's Restaurant

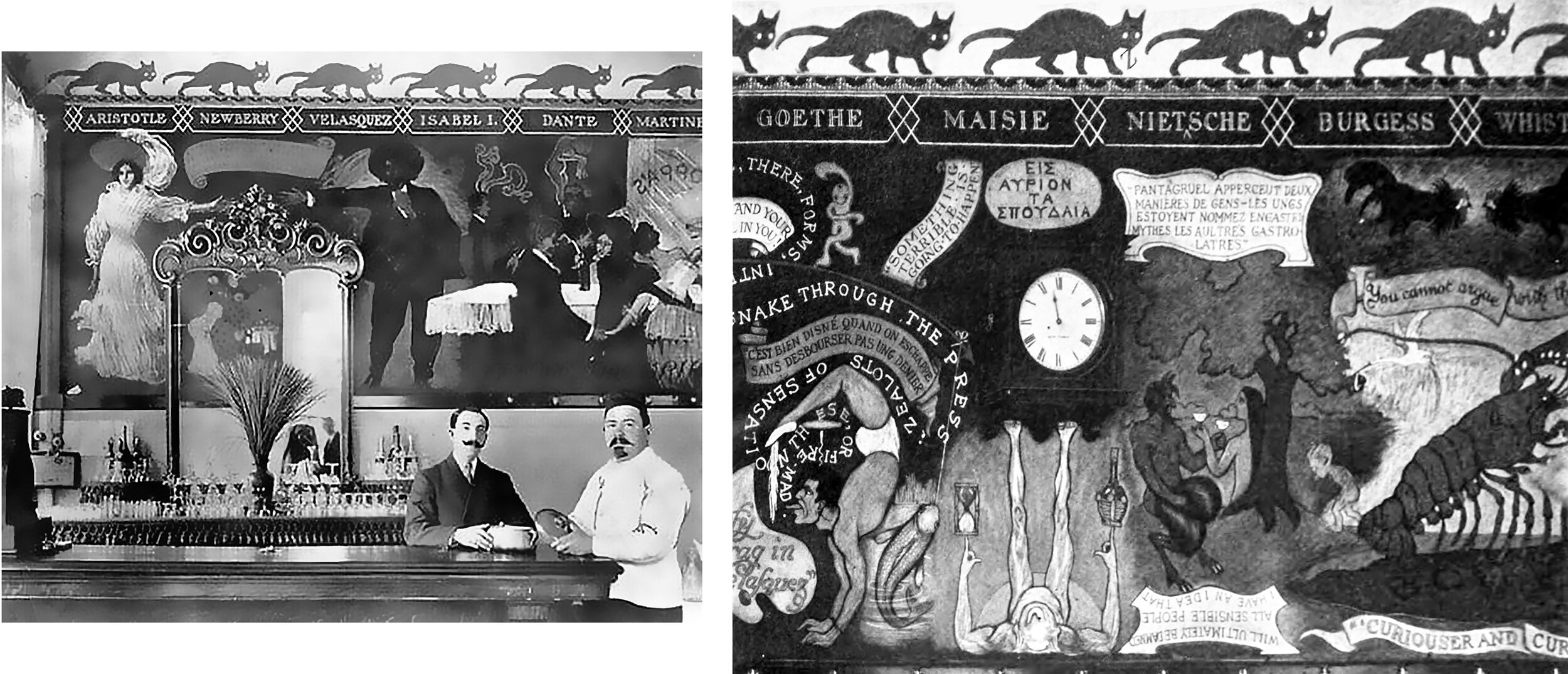

Coppa's restaurant in the old Montgomery Block, c. 1910, Photo: San Francisco Historical Society

Original Coppa’s Restaurant was located in the Montgomery Block (aka “Monkey Block”) in San Francisco’s Barbary Coast. Coppas was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake but Montgomery Block was not. Today the Transamerica Pyramid occupies its former location.

Coppa’s was famous for it’s murals that were described in The Coppa Murals by Warren Unna, A Pageant of Bohemian Life in San Francisco at the Turn of the Century, The Book Club of California 1952

I think of one who tried like that to unfold

the margin of his life where it was curled,

to see into the shadows shot with gold

that lie in iris hues about the world.

Because he dared to touch the sacred rim,

does God resent this eagerness in him?

Poem fragment: George Sterling by Jack London

In late June of 1905, Sterling arrived in Carmel-by-the-Sea with two friends from San Francisco, who helped him build his home. While they constructed his house, they all lived in a tent. The Sterlings’ bungalow was in the Arts and Crafts, or Craftsman Style, with a wood-shingled exterior and a porch. In the woods behind his house, he created a “pagan altar”, made of cattle or horse skulls, which were hung on trees.***

There was no town at Carmel then; nothing but a farm or two, one or two graceless buildings, and the wild beach and sunny dunes.

Sterling delighted to go striding, axe on shoulder, over Monterey hills looking for pitch pine or bee trees or whatever arduous and practical simplicities restored him to the human touch…or the lot of us would pound abalone for chowder around the open-air grill at Sterling’s cabin…*

The Carmelites’ picnic on Point Lobos, Gale cartoon from article by Wright, Willard Huntington, "Hotbed of Social Culture, Vortex of Erotic Erudition," Los Angeles Times, May 22, 1910. Left to right: Jack London, Alice MacGowan Cooke, Upton Sinclair, Xavier Martinez, Mary Austin, George Sterling, Lucia Chamberlain, Fred Bechdolt, James Hopper, Fra Henry Lafler.

*Romantic Rebels by Emily Hahn, quoting Mary Austin

***Carmel-By-The-Sea, the Early Years (1903-1913): An Overview of the History ...By Alissandra Dramov

A Wine of Wizardry

Without, the battlements of sunset shine,

’Mid domes the sea-winds rear and overwhelm.

Into a crystal cup the dusky wine

I pour, and, musing at so rich a shrine,

I watch the star that haunts its ruddy gloom.

Now Fancy, empress of a purpled realm,

Awakes with brow caressed by poppy-bloom,

And wings in sudden dalliance her flight

To strands where opals of the shattered light

Gleam in the wind-strewn foam, and maidens flee

Sterling’s poetry can be sentimental harkening back to Shelley and Keats, but he could also muster the dark power realized by Poe and Baudelaire and his reverence for nature experienced - as opposed to nature idealized anticipates the writings of poet Robinson Jeffers.

italics: George Sterling's 'Wine of Wizardry' sparked a clash of critics, Essay by Geoffrey Dunn on sfgate.com 2007

A Wine of Wizardry and Other Poems by George Sterling can be found on Google Books.

George Sterling wreathed with a Laurel Crown on the wall of Coppa’s Restaurant.

George Sterling’s legacy lies not in his poetry, all his written work is out-of-print. He is remembered, however, as the catalyst to the creation of the artists colony in Carmel. A gentler Prospero conjuring magic in the moonlight on hoary cypress and rocky shoreline.

From Spiritual Retreats to Glamping (7)

The list of lecturers who participated at Esalen in its early days reads like a Who’s Who of avant-garde thinkers, artists, psychologists, and philosophers. It includes Erik Erikson, Ken Kesey, Alan Watts, John Lilly, Buckminster Fuller, Aldous Huxley, Linus Pauling, Fritz Perls, Joseph Campbell, Robert Bly and Carl Rogers. They were joined by musicians George Harrison, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Crosby Stills Nash & Young and other kindred souls.*

The Big Sur Folk Festival 1964-1971

The festivals were founded by Nancy Carlsen.

*The Esalen Institute And The Human Potential Movement Turn 50 by Debra Ollivier, Huffungton Post

Big Sur’s wild scenic beauty is host to many places catering to spiritual solace. Esalen’s with its credo of “Religion of no religion” is close to two other major retreat centers. The New Camaldoli Hermitage is a Benedictine Hermitage in the Santa Lucia Mountains that offers silent, undirected retreats. The Tassajara Zen Mountain Center: Tassajara Hot Springs is a collection of natural hot springs in the Ventana Wilderness, within the Santa Lucia Range and Los Padres National Forest in Monterey County, California. The hot springs have been the site of various resorts since the 1860s. Since 1967, the hot springs have been the site of a Buddhist monastery which is opened to visitors during the summer months only.*

* description: Tassajara Hot Springs sitting area by the front office. * photographer: Earthworm * photographer location: San Francisco Bay Area, CA * photographer_url: [http://www.flickr.com/people/earthworm/] * flickr_url: [http://www.flickr.com/photos/

Rustic cabins and family campsites aside, there are luxury accommodations in Big Sur. The Post Ranch Inn serves the wishes of the wealthy travelers and The Ventana Big Sur hosts corporate retreats, executive summits and offers tent cabins in the redwoods with fire pits, catered meals, yoga classes, sommelier wine & cheese hour and evening bed turn-downs on a premium mattress and linens called Glamping.

But of course there is always outright ownership of an A frame home on a bluff overlooking the Pacific ocean.

Big Sur Creeks and Rivers (6)

Limekiln Creek is a vital habitat for southern steelhead trout, the entire Limekiln and Hare watershed is free flowing. Part of the family Salmonidae, which includes salmon and trout, steelhead are the anadromous form of rainbow trout, which means the fish are born in freshwater and migrate to the ocean as adults.*

*Hiking & Backpacking Big Sur by Analise Elliot

The Big Sur mountains and canyons were once shamelessly exploited for its natural resources. Clearcutting redwoods and extensive mining threatened the natural beauty of the landscape.

Limekiln Canyon has four stone and iron furnaces that were built at the base of a large talus slope eroding from a limestone deposit. Limestone rocks were loaded into the kilns, where very hot wood fires burned for long periods to purify the lime.**

The lime was packed into barrels, hauled by wagon to Rockland Landing on the coast and loaded onto ships that carried it to northern ports for use in concrete.**

After only three years, the limestone was all but depleted, as was the redwood forest that had been nearly clearcut to use for lumber and fuel. Today the four kilns, some stone walls, and bridge abutments are the only remains of the once-thriving lime industry.** The forest is restored, the redwoods in the area have returned and new growth sprouts victorious out the top of the rusting kilns.

**Textual information from the Limekiln State Park published by California State Parks

Little Sur River

The river mouth and lower Little Sur watershed are private property and are not open to the public. They are visible by using the pull-outs on the southern end of Highway 1. The Little Sur area’s most pristine rivers. It has one of the best steelhead trout runs along the coast, and great blue herons and belted kingfishers hunt in its pools and eddies.*

The Natural History of Big Sur by Paul Henson and Donald J. Usner

Big Sur River

The Big Sur River is a long, relatively gentle watercourse in spite of the fact that it cuts through very rugged terrain. The Big Sur watershed is the largest coastal drainage in the Big Sur area, draining about 60 square miles of steep terrain in the heart of the north-central mountains.*

The Natural History of Big Sur by Paul Henson and Donald J. Usner

Julia Pfeiffer State Park - McWay Falls

Santa Lucia Mountains and the legend of Los Vigilantes Oscuros (5)

The Dark Watchers (also known by early Spanish settlers as Los Vigilantes Oscuros) is a name given to a group of entities in California folklore purportedly seen observing travelers along the Santa Lucia Mountains.

The Dark Watchers are described as tall, sometimes giant-sized featureless dark silhouettes often adorned with brimmed hats or walking sticks. They are most often reported to be seen in the hours around twilight and dawn. They are said to motionlessly watch travelers from the horizon along the Santa Lucia Mountain Range. According to legend, no one has seen one up close and if someone were to approach them, they disappear.*

The mountains extend parallel with the coast from Monterey southeast for 105 miles to San Luis Obispo. Competing with the riveting spectacle of a winding road with vertiginous cliffs plunging to the shimmering Pacific Ocean with an undefined horizon, the highway hangs on the enormous shoulders of the Saint Lucia Mountain Range.

Lush ferns, newts, slamanders, and the southernmost stretch of redwoods all thrive in the wet ravines. Chaparral and coastal scrub cover more than half of the San Luca Mountains, with yucca plants from souther deserts, lupine, sagebrush, and manzanita growing on the drier slopes. Together, these two zones provide habitat for mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, deer, squirrels, and numerous other animals.**

Mount Manuel from Buzzard’s Roost Trail

*Dark Watchers/Wikipedia

**Big Sur, The Making of a Prized California Landscape by Shelley Alden Brooks

The Ventana Wilderness of Los Padres National Forest is a federally designated wilderness area located in the Santa Lucia Range. This view is from the terrace of The Sur House looking south.

The slopes of the coastal highlands receive the most water from orographic rainfall, or rain that occurs when moisture-bearing clouds are forced to higher elevations. During the dry summer months, the trees collect most of their water from adsorption and condensation of moisture in prevailing fog and low ceilings. Redwoods revive about 35 percent of their water from the air. A large redwood can consume up to five hundred gallons of water a day.*

Orographic cloud belts can produce Atmospheric Rivers, (a term coined in the 1990s), that produces massive amounts of rainfall undermining watersheds and creating the rockslides that close Highway 1.

Orographic lift of moist air coming off ocean produces clouds along the Santa Lucia Range, of the California Coast Ranges System, NOAA Photo Library, Robert Schwemmer, NOAA, NOS, CINMS.

*The Centennial: A Journey through America’s National Park System by David Kroese

Protected areas of Big Sur (4)

Inaccessible beaches and coastal marine habitats are part of the Big Sur landscape. Large coastal marine conservation areas flank the central California coastline off Big Sur:

In the waters adjacent to Andrew Molera State Park there are two MPAs (Marine Protected Areas), Point Sur State Marine Reserve (SMR) and Point Sur State Marine Conservation Area (SMCA). The Big Creek Marine Conservation Area covers Big Sur’s southern coast.

Off this remote stretch of coastal highway, underwater canyons and submerged mountain ridges shape the ocean floor. These topographical wonders create conditions for marine life to thrive. Here ocean currents bring nutrient-rich waters closer to shore, and fish, sea birds and invertebrates flourish.

Many species of fish live in the rocky tide pools, kelp forests, sandy bottoms and deep canyons off Point Sur. Cabezon, vermillion rockfish and blue rockfish hide among the kelp, while mola mola (sunfish) may be found basking on the surface offshore.*

A kelp forest grows towards the ocean surface; its canopy seeks the sunlight like the ancient redwoods in Big Sur’s mountain canyons. Bull Kelp can grow as much as 2 feet in one day.

NOAA’s National Ocean Service

Bull Kelp is common in the Big Sur coastal marine preserves. Bulbous heads allow the kelp stalks to reach the surface.

Partington Cove & Pfeiffer State Beach

Partington Cove is a small indentation in the rocky shoreline, but it is one of the most dramatic bits of coastline accessible along the Big Sur coast south of Point Sur.*

Partington Cove: The clearness of the water is a consequence of the hardness of the granite rock; little sediment erodes from this rock to cloud the water.*

*The Natural History of Big Sur by Paul Henson and Donald J. Usner

Partington Cove

Pfeiffer State Beach Lagoon

Pfeiffer State Beach: Early morning fog rolls in.

Pfeiffer State Beach: Semi-secluded north end of the beach.

Pfeiffer State Beach: Franciscan rock.

Pfeiffer State Beach: Franciscan rock layers pushed into a vertical orientation.

Pfeiffer State Beach: The keyhole that framed a thousand sunsets.

The Big Sur coastline looking south from Nepenthe.

![* description: Tassajara Hot Springs sitting area by the front office. * photographer: Earthworm * photographer location: San Francisco Bay Area, CA * photographer_url: [http://www.flickr.com/people/earthworm/] * flickr_url: [http://www.flickr.com/p…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57c769f1ebbd1a73645d0e19/1568567962052-LZUMYPWI20XR4A39GTU3/Screen+Shot+2019-09-15+at+10.07.09+AM.png)