Family vigils on the first night of Día de Muertos (29)

Young woman masquerading as La Llorona (29)

A young woman dances alone among swirling couples near the Zocalo in downtown Oaxaca. She would stop dancing long enough to stare out with a chilling, angry look. La Llorona is a legendary ghost figure in Mexican folklore.

The week long fiesta of Día de Muertos is a popular time to dress like famous ghosts of regional lore.

La Llorona ("The Weeping Woman") is a legendary ghost prominent in folklore of Latin America. This myth has a tendency to take aspects of an urban legend and is present throughout Mexican culture. According to the tradition, La Llorona is the ghost of a woman who lost her children and now cries while looking for them in the river, often causing misfortune to those who are near or hear her.

Though several variations exist, the basic story tells of a beautiful woman by the name of María who drowns her children in a river as a means of revenge towards her husband, who had left her for a younger woman She drowns herself in the river when she realizes her children are dead.

At the gates of heaven, she is challenged over the whereabouts of her children, and is not permitted to enter the afterlife until she has found them. María is forced to wander the Earth for all eternity, searching in vain for her drowned offspring.

She constantly weeps, hence her name "La Llorona."

She is caught between the living world and the spirit world.

(Wikipedia)

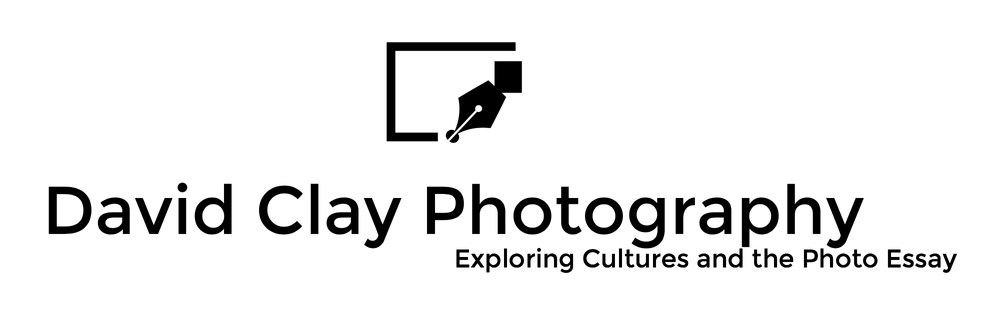

Movies, theater musicals and books about this Mesoamerican legend

Tlanchana (La Sirena)

The traditional representation of the Tlanchana is in clay. Its shape is half fish, crowned and with flowers, playing a guitar. Here are representations of mermaids and mermen.

The legends of the mermaids of Mexico take place in terrestrial waterways like lakes, lagoons and rivers.

The Atl-tonan-chane, the Tlanchana or mother Lanchana, is the woman goddess inhabitant of water. Source: Sirena de tule of Jorge Arzate by Felix Suarez

Alebrije Tlanchana

Image attribution: The Spirit of Folk Art, The Girard Collection at the Museum of International Folk Art by Henry Glassie.

Mermaid Jar. San Bartolo Coyotepec, Oaxaca, Mexico. Painted earthenware, 20” high

María de la Soledad on the altar in Santa Domingo Church in Oaxaca

Our Lady of Solitude is the patroness of Oaxaca.

Our Lady of Solitude (Spanish: María de la Soledad) is a title of Mary (mother of Jesus) and a special form of Marian devotion practised in Spanish-speaking countries to commemorate the solitude of Mary on Holy Saturday. Variant names include Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, Maria Santisima, Nuestra Señora Dolorosisima de la Soledad, and Virgen de la Soledad.

María de la Soledad's feast day is celebrated on December 18 in Spanish-speaking countries.

(Wikipedia)

María de la Soledad in Oaxaca dressed with with lace cloth.

The teaching that Mary intercedes for all believers and especially those who request her intercession through prayer has been held in the Church since early times, for example by Ephraim, the Syrian “after the mediater a mediatrix for the whole world. Intercession is something that may be done by all the heavenly saints, but Mary is seen as having the greatest intercessionary power.*

*Catholic Mariology>Wikipedia

A Marian Apparition is a reported supernatural appearance by the Blessed Virgin Mary. The figure is often named after the town where it is reported, or on the sobriquet given to Mary on the occasion of the apparition.

Marian apparitions sometimes are reported to recur at the same site over an extended period of time. In the majority of Marian apparitions only one person or a few people report having witnessed the apparition.

Official Catholic accounts claim that the Virgin Mary appeared four times before Saint Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin. The panels on the left and right in the image below represent the four appearances of the Virgin to Juan Diego.

(Wikipedia)

Reredos dedicated to the story of The Virgin of Guadalupe in Oaxaca, Mexico

The cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe appears to go back to the second half of the sixteenth century, although efforts to codify her origins only occurred in the mid-seventeenth, when a strong sense of Creole identity crystallized in New Spain. The story of her four apparitions to the pious Indian Juan Diego in 1531 are well known, as is the stubborn disbelief of Bishop Juan de Zumarraga until proof was brought in the form of Juan Diego’s mantle filled with extraordinary flowers that, once emptied out, revealed the image of the Virgin imprinted in the mantle.*

*The Arts in Lain America 1492-1820

Juan Diego by Miguel Cabrera, Museo Regional de Queretaro, Mexico

Devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe originated with the image miraculously impressed onto the garments of the Indian Juan Diego. The holiness of this image obliged all those painters who wished to copy it to reproduce it as exactly as possible, in many cases even respecting its original dimensions. Many painters used tracing techniques to ensure precision in details, and no painter felt capable of reproducing pictorially what the hand of God had made. When the new version was finished, it was “touched” to the original to transmit its miraculous properties to the copy. Starting in the seventeenth century, but especially throughout the eighteenth, cartouches were added to the corners of the image to narrate the apparition story.*

*The Arts in Latin America 1492-1820

Virgin of Guadalupe by Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz (Mexican, 1713-c.1772)

Casta paintings were a new, secular art form primarily produced in eighteenth-century Mexico. A notable exception to the secular nature of the genre is Luis de Mena's 1750 painting of Virgin of Guadalupe with castas.*

About race, rather than the local hierarchies that the English word “caste” defines, there paintings addressed the complex racial mixing that occurred in viceregal society. From the moment of the Spanish conquest, miscegenation among the Spaniards, Africans, and Indians created a society of racial types, beginning with familiar ones such as mestizo (Spaniard and Indian) and mulato (Spaniard and African). The families depicted in casta paintings are shown in both indoor and outdoor settings, so that the genre provides a multitude of information about daily life in New Spain, including food, clothing, and entertainment. In their abundant details, these paintings sent a message to the mother country (for most of the series seem to have been intended for export to Spain) of the material wealth and natural abundance of the viceroyalty. In doing so, they reflect the growing consciousness of what it meant to be Mexican, and the emergence of a nationalism that would one day lead to independence. **

*Wikipedia

**The Arts in Latin America 1492-1820

Notes on Caste and Ethnic Identity in Modern Mexico

In Oaxaca, as in many other parts of Mexico, who one “is,” in terms of one’s social prominence or character, has everything to do with one’s origins, usually biologically understood. Such understandings may be vestiges of the colonial period, when social status was determined by legal caste designations premised on “racial” origins and informed by physical appearance and occupational status—to which were ascribed typical manners and morals.

Oaxacans of any “ethinc” background exhibit a strong affinity with their places of birth and will identify others in the same way. When asked for her “ethnic” affiliation, a person of indigenous origin is not likely to say “Zapotec” or “Mixe,” but, instead, to name the region or the town she is from. A person is a serrana (from one of the sierra regions of the state) before she is a oaxaqueña. This form of identification carries over into the national sphere, where politicians are always identified by the states they come from; such points of geographic origin are considered to be deeply significant aspects of their identities.*

*Days of Death, Days of Life by Kristin Norget, Columba University Press 2006

Painting a large Alebrije Angel

Visiting workshops producing modern folk art based on traditional practices are a feature of tourism in the Oaxaca region. A large-scale carved wooden religious figure is hand-painted with vibrant colors and finely-wrought decorative detail. On the back are two prominent holes are made to attach celestial wings.

Tapete de Levanada de la Cruz in the Panteon Nuevo (28)

Tapete de Levanada de la Cruz are sand sculptures, they are like colored "carpets" made from dyed sawdust, sand, seeds, and flower petals. While Dia de Muertos is primarily a pagan celebration. there is significant acknowledgment and even participation by the Catholic Church. Here, representations of Jesus Christ are votive statements of a prominent local family.

Representations of Jesus Christ and popular Saints are used for deceased male relatives and the Virgin Mary, (usually in the form of the Virgin of Guadalupe) are used for females.

Music for Día de Muertos (27)

Son mexicano is a category of Mexican folk music and dance that encompasses various regional genres, all of which are called son. The term son literally means "sound" in Spanish. Mexican son likely originated in Veracruz with major son traditions in this state along with the La Huasteca region, the Pacific coast of Guerrero and Oaxaca, Michoacán and Jalisco (where it morphed into mariachi).

As a base, son music in Mexico has the Baroque music of Spain, along with African and indigenous elements.

Chilena music and dance is native to the coastal areas in the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca, which has a large Afro-Mexican community. Local legend has it that the “chilena” music and dance came from people from Chile who came to the shore of Guerrero after their ships were attacked by pirates.*

Oaxaca has a musical tradition/style known as Son Istmeño, which is a continuation of the son folk tradition found throughout Mexico (as well as Cuba and Puerto Rico). It has very strong indigenous roots, and the songs are sung in both the Zapotec language as well as Spanish; the rhythms are often indigenous as well, while the basic melodic/harmonic structure is Spanish. The song "La Llorona" is an example of a son istmeño. Marimba ensembles are also found here.

Wikipedia

Entrance to the Panteón Viejo (Old Cemetery), Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán, Mexico

Oaxaca also has many traditional Brass Bands, sometimes called Tambora Oaxaqueña, the music is very similar to the Balkan Music, and it is believed that they are both from the same roots. Bakanic composer, Goran Bregovic, made concerts in Mexico, with bands from Oaxaca.**

There are two cememteries, here, the Panteon Viejo (old cemetery) and the Panteon Nuevo (new cemetery).

In the two sections of this pantheon there are more than 3 thousand tombs that are visited annually by relatives, acquaintances and national and international tourists who are interested in capturing the moment and living the tradition of the Day of the Dead.*

*Source: https://www.nvinoticias.com/nota/73887/apuntalan-panteon-viejo-de-xoxocotlan-oaxaca

**Wikipedia

Panteon Nuevo

Panteon Nuevo

Bandstand near the Zócalo in Oaxaca City

Velada at the Panteón Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán and Tourists (26)

Panteon Viejo (Old Cemetery), Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán, Mexico

Día de Muertos and the Christmas season are compelling visual events that attract tourists from around the world to Oaxaca. The first evening of Día de Muertos there are more foreign visitors in the cemetery of Xoxocotlán than local families holding vigils.

Family Eating tamales at Xoxocotlan cemetery (25)

Panteón Viejo (Old Cemetery), Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán, Mexico

The graveside vigils start in the early evening and continue all night. It is a tradition that the favorite food and drink of visiting souls are shared at the first night’s vigil.

The dead do not live in the cemetery, it is considered common ground where the living and the departed souls can gather together.

Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán Cemetery (24)

Panteón Viejo (Old Cemetery), Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán, Mexico

A statue of a Saint is called a Santo.

On 31 October, exactly at 3pm, church bells ring a chorus called “Los Angelitos” (little angels) and braziers with copal burn by the altars. This is to welcome the souls of the deceased children who come to visit until 3pm the next day. On the 31st at 11pm at the Church of Santa Elena de la Cruz, a procession with an image of San Sebastian winds through the streets to the Panteon Viejo (Old Cemetery) where the first chapel built for the community was constructed in the 17th century. Here candles, prayers and songs are offered for all the dead.

A Catholic brotherhood known as “La Capilla” holds a prayer service accompanied by Latin chants.

Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom by arrows recalls the uncertainty of life, and the abruptness of death.

Ceremony outside the ruins of the San Sebastián chapel.

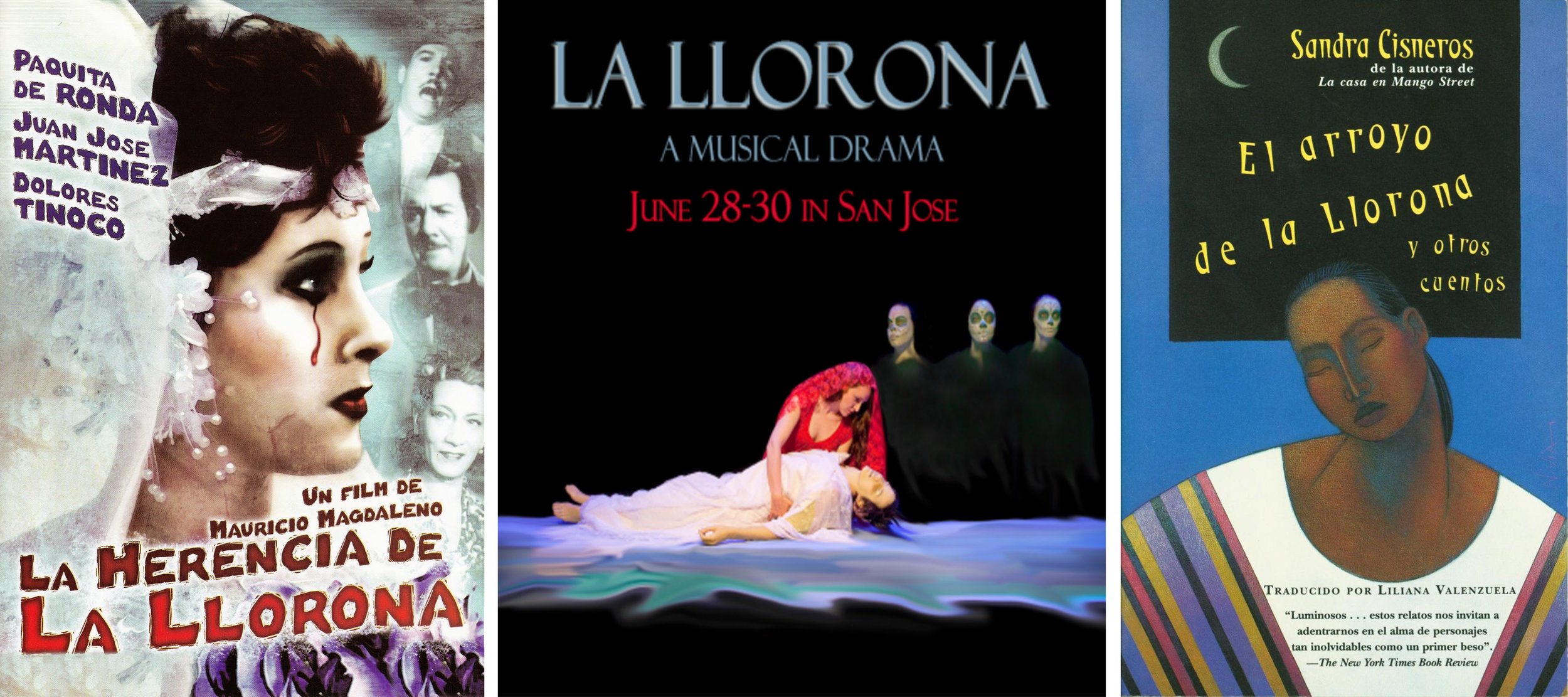

The two most important celebrations held in the municipality are “martes de brujas” or Witch Tuesdays and Day of the Dead. Tuesdays during Lent are called the “martes de brujas” or Witch Tuesdays. On these days, tamales with panela cheese are sold along with atole. The fourth Friday of Lent is called the Friday of the Samaritan, which is celebrated in the atrium of the town church with the sounds of bells, music and fireworks. The event ends with Mass. Lent ends with Holy Week, which includes a Passion Play. The fourth Tuesday in Lent has been host to an annual musical event called the Martes de Brujas since 2005. In 2009, the event included groups such as Sonora Santanera, the Dueto de Cuerdas de Oaxaca, El Grupo de Danzón and Lizet Santiago. The tradition of “Witch Tuesdays” dates back to the colonial period when Friar Domingo de Santamaría promoted the construction of a church with volunteers working nights. Women would come to offer tamales and atole to the volunteers, lighting their way with a type of lamp called a “bruja”, which contained a candle protected by paper shields. The consumption of tamales on these Tuesdays has been practiced since but in the 1970s, cultural events began to accompany the ritual.

Text from Wikipedia

Copal Incense and Día de Muertos (23)

The word copal is derived from the Nahuatl language word copalli, meaning incense. Copal incense is burned on Día de Muertos to guide the dead back to their homes. The incense is somewhat smoky when burned and has sort of a pine scent. The copal was offered by the indigenous peoples of the Oaxaca region to their gods and is used to cleanse the place of evil spirits and thus the soul can enter your house without any danger.

Copal incense is sold in bulk in community markets in the Oaxaca region. A number of hardened tree resins are used as aromatic incense, these resins are considered the "blood of trees".

Copal incense is typically burned over charcoals in a tripod brazier. In the Zapotec world, smoke is what translates material things from our world into the spirit world.

Día de los Inocentes: Day of the Innocents (22)

Tapetes de Arena (sand tapestry) of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

November 1st is referred to as Día de los Inocentes (Day of the Innocents), a day to celebrate los angelitos (little angels), the souls of children that have passed away.

November 2nd is known as Día de los Difuntos (Day of the Deceased).

A mixture of the macabre and whimsey: a cemetery memorial to a beloved child is composed with a powder-blue crib, a winking “Felix the Cat” balloon, fresh flowers, and a basketball and hoop. Halloween decorations make an appearance as well, orange jack-o-lanterns, a spider and a paper ghost.

Though the souls are “in glory”, they still have human feelings.

Zapotec by Helen Augur, Doubleday and Co. 1954

A simple grave marker commemorates the recent death of a child.

Oaxaca and the surrounding southern states have the highest rates of infant mortality (children under the age of 1 year) in Mexico. For children pneumonia is still a leading cause of death.* The lack of access to healthcare services is a secondary cause. Many births take place in the home without skilled medical attendance; and many give birth completely alone in their homes.**

*World Health Organization, Mexico’s quest for a complete mortality data set, https://who.int

**Preventable infant deaths, lone births and lack of registration in Mexican indigenous communities: health care services and the afterlife of colonialism by Jennie Gamlin and David Orsin

Source: geo-mexico.com

Candles lighted for Día de Muertos (21)

The Muertos live in a world of darkness. The living provide light with candles as another pathway home.

Día de Muertos, The Journey back home (20)

Many villages build ceremonial arches covered in marigolds with pathways marked with flowers to guide and welcome deceased relatives back home during Dia de Muertos.

The celebration of the festival Dia de los Muertos (alternately known as Dia de Muertos and Dia de Todos Santos) corresponds to the observance of Hallowe'en (or the Feast of All Saints and All Souls) in other countries with significant Catholic populations. These Catholic feast days, October 31-November 2, take on a unique expression in Mexico. As complex as the culture of Mexico itself, Dia de los Muertos is a fusion of pre-Columbian religious traditions (Olmec, Mayan, Aztec).

In Mexico, people die three legendary deaths, the third being the most poignantly final. The first death is the failure of the body. The second is the burial of the body. The most definitive death is the third death. This occurs when no one is left to remember us.

Source: https://www.albany.edu/~dkeenan/isp523/halloween.html

Comparsa in Oaxaca for Día de Muertos (19)

Twilight in Oaxaca. Raucous street parades fueled with music from brass bands, fireworks and plenty of mescal are found everywhere.

Comparsas are parades put on by schools and civic organizations to put their own stamp on Día de Muertos.

Quinceañera in Oaxaca

A young woman dressed in a white blouse and voluminous pink skirt is seated in the center aisle before the altar. She will be the focus of attention throughout the day from the early morning mass to the day long party that follows.

The fiesta de quince años (also fiesta de quinceañera, quince años and quince) is a celebration of a girl's 15th birthday. It has its cultural roots in Mesoamerica and is widely celebrated today throughout the Americas. The girl celebrating her 15th birthday is a quinceañera (Spanish pronunciation: [kinseaˈɲeɾa]; feminine form of "15-year-old"). In Spanish, and in Latin countries, the term quinceañera is reserved solely for the girl. (Wikipedia)

The celebrations of Dia de Muertos do not overshadow other important events. Weddings and coming-of-age rites are commonplace in the churches and colorful fiesta parades in the streets are seen all over the Oaxaca region.

One of many tributes to Benito Juárez in Oaxaca, Mexico

Benito Juárez is remembered as being a progressive reformer dedicated to democracy, equal rights for his nation's indigenous peoples, his antipathy toward organized religion, especially the Catholic Church and what he regarded as defense of national sovereignty. The period of his leadership is known in Mexican history as La Reforma del Norte (The Reform of the North), and constituted a liberal political and social revolution. (Wikipedia)

Juárez was a Zapotec indian from the Oaxaca area of Mexico. He was the first leader of Mexico to attempt to address the needs of the ethnically diverse territories of a modern state. Mexico has a mixed population of Criollos (Latin Americans of full or near full Spanish descent), Indios (Indigenous peoples of the Americas), and Mestizos (people of mixed race, especially the offspring of a Spaniard and an American Indian).

Papier-mâché skulls at popular restaurant in the Oaxaca region (18)

Cartonería or papier-mâché sculptures are a traditional handcraft in Mexico. The papier-mâché works are also called "carton piedra" (rock cardboard) for the rigidness of the final product. These sculptures today are generally made for certain yearly celebrations, especially for the Burning of Judas during Holy Week and various decorative items for Day of the Dead. However, they also include piñatas, mojigangas, masks, dolls and more made for various other occasions. (Wikipedia)

European influences on Día de Muertos (17)

Long before the uses José Guadalupe Posada made of calaveras, a long tradition of illustrating dancing skeletons for the purposes of political and social satire existed in Germany and England.

In the Danse Macabre, or Dance of Death, skeletons escort living humans to their graves in a lively waltz. Kings, knights, and commoners alike join in, conveying that regardless of status, wealth, or accomplishments in life, death comes for everyone. Source: altasobscura.com

Arranged in four rows are twenty-four figures, all protesting at being seized by Death, a skeleton. Words are engraved above the head of each speaker. Death is throughout in the attitude of a fantastic dancer, handling some of his partners roughly or grotesquely, the skull registering grisly amusement. Description from the British Museum website

The Broad Way

The way of life is narrow, that of perdition is broad, rosie and pleasant; there we must climb up a craggy clift, here we slide downe easily into a dale. (Virgil)

Time and the Devil strut vigorously at the head of the parade, while Death on the sidelines strikes up the tune. And behind them in a meandering crocodile follows the vast rout of humanity.

The Emblem by John Manning

The theme of the 'Three Living and the Three Dead' is a relatively common form of memento mori in mediaeval art. In the poem, an unnamed narrator describes seeing a boar hunt, a typical opening of the genre of the chanson d'aventure. Three kings are following the hunt; they lose their way in mist. ('Starting out of a wood') three walking corpses appear, described in graphically hideous terms. The kings are terrified, but show a range of reactions to the three Dead, ranging from a desire to flee to a resolve to face them. The three corpses, in response, state that they are not demons, but the three kings' forefathers, and criticise their heirs for neglecting their memory and not saying masses for their souls.

The final message of the Dead is that the living should always be mindful of them - "Makis your merour be me" (120) - and of the transient nature of life. (Wikipedia>Three Dead Kings)

Photo- © Jörgens.Mi:Wikipedia, Licence- CC-BY-SA 3.0, Source- Wikimedia Commons.jpg

The Tree of Man’s Life by John Goddard, ca. 1639 - 50

The Tree of Man's Life, or an Emblem declareing the like, and unlike, or various condition of all men in their estate of Creation, birth, life, death, buriall, resurrection, and last Judgement.

Allegorical account of the life of man, showing a tree, with its roots and its branches bearing texts from the Bible; at the top the irradiated name of Christ with the saved in heaven and angels seated on a semi-circle of clouds; intertwined branches of the tree form two ovals, the upper containing the figure of Death with a funeral scene.*

*britishmuseum.org

Original image of engraving on the right.

Portrait of Man - Memento Mori

In art, memento mori are artistic or symbolic reminders of mortality. All memento mori works are products of Christian art. In the Christian context, the memento mori acquires a moralizing purpose. To the Christian, the prospect of death serves to emphasize the emptiness and fleetingness of earthly pleasures, luxuries, and achievements, and thus also as an invitation to focus one's thoughts on the prospect of the afterlife.

Another manifestation of memento mori is found in the Mexican "Calavera", a literary composition in verse form normally written in honour of a person who is still alive, but written as if that person were dead. These compositions have a comedic tone and are often offered from one friend to another during Day of the Dead.*

Wikipedia

Andrea Previtali called Cordelighi

With the Spanish colonization of Mexico, came the European iconography of Death. Death usually portrayed as a skeleton carrying a scythe and an hourglass and often wearing a hooded cloak.

In 1792, Fray Joaquín de Bolaños, a friar from Zacatecas, published a fantastical work called “The Portentous Life of Death…” The accompanying engravings by Francisco Agüera Bustamante, were not terrifying and solemn like the European imagery, but were humorous, even frivolous.*

*The Day of the Dead, A Pictorial Archive of Dia de los Muertos, selected and edited by Jean Moss, Dover Publications